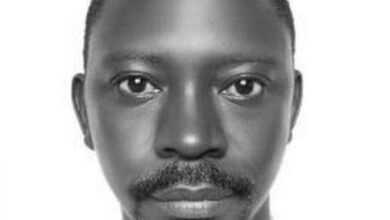

Former PM Dr. Rugunda explains his Bududa background

Many Bakiga visiting Bududa, especially in Bukigai and Bushika, openly say, “We are home; we are one people.”

Op-Ed: Half a century ago, Bulucheke Sub-county in present-day Bududa District was a boiling point of revolutionary thought. It was a centre where young political minds gathered to interrogate ideology, power, and Africa’s future. Among those who trotted the hills of Bulucheke were figures who would later become national political heavyweights, including Dr. Ruhakana Rugunda and Magode Ikuya, drawing political cues from Bulucheke’s revolutionary strongman, Natolo Masaba.

At a time when many of today’s youths are trapped in narcotics and alcohol and unable to reason beyond village backyards, a young Ruhakana Rugunda trekked nearly 600 kilometres from Kigezi to Bugisu in search of Marxist and communist thought. He was driven by a deep determination to fight oppressive regimes alongside other actors who shared a common revolutionary ideology.

Recently, while attending a workshop in Kampala organized by the Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy, I ran into Dr. Ruhakana Rugunda, one of Uganda’s most respected political figures. True to his lifelong principles, he greeted me without honorifics: “Ndugu Masiga, how is Bugisu?”

After exchanging pleasantries and upon learning that I now serve as the Spokesperson of the Bugisu Cultural Institution an institution that unites the Bamasaaba under a gazetted cultural leader Dr. Rugunda revealed that he comes from Bulucheke Sub-county and grew up there in Manjiya County during the 1970s.

Dr. Rugunda’s Christian name has never been given prominence, a trait typical of Marxist-Leninist intellectuals of his generation. His early political associations with Marxist and communist thinkers from Bugisu such as Natolo Masaba, Prof. Dani Nabudere, and Maumbe Mukhwana shaped this outlook. Many of these thinkers deliberately downplayed Christian names in favour of African ones.

Marxist and communist intellectuals of that era, including Dr. Rugunda and his peers, were also reluctant to use honorifics such as Doctor, Professor, or Honourable. In their estimation, such titles were foreign and capitalist in origin symbols of elitism associated with exploitation. Titles, they believed, created distance between leaders and the mwananchi, whom they sought to protect and represent. By rejecting pomp and embracing African names, they aimed to promote equality in line with socialist principles.

Dr. Rugunda first encountered Natolo Masaba’s revolutionary ideas in the 1960s, while he was a student at Mwiri College, Jinja. At the time, Mwiri was a prestigious institution that produced leaders who later played key roles in liberation movements across Africa.

Masaba’s Marxist and socialist reasoning deeply influenced the young Rugunda. Together with contemporaries such as Yoweri Museveni, Magode Ikuya, Maumbe Mukhwana, and Macho Chango, they viewed capitalism through the lens of Marxism as an exploitative colonial system. They regarded the leadership of the time as complicit in colonial and capitalist oppression and resolved to dismantle it in order to create a new revolutionary order.

Many of these young men, then in their twenties, were deeply immersed in revolutionary literature on socialism and communism. Some received ideological or military training in Russia and China, while others belonged to political clubs across Africa. They absorbed the ideas of Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, and Fidel Castro, and were determined to confront and overthrow oppressive leadership.

Like Dr. Rugunda, Natolo Masaba was profoundly disturbed by the suffering Africans endured under colonial rule in countries such as Mozambique and Zimbabwe, as well as Asians in Vietnam. They devised ways to support liberation struggles and reclaim the right of oppressed peoples to self-governance.

Dr. Rugunda recalls making many foundational visits to Bulucheke Sub-county in the 1960s and 1970s. This account is corroborated by Hon. Magode Ikuya, who, during the burial of Joseph Kutosi, a FRONASA supporter in Bulucheke last year, stated that they frequently visited Natolo Masaba’s home with Dr. Rugunda to discuss political liberation strategies and international affairs.

These meetings did not go unnoticed by the state. Like a scene from George Orwell’s 1984, the Idi Amin regime closely monitored every discussion and movement involving Rugunda and his comrades. Persistent surveillance and pressure from state security agencies eventually forced him into exile—first to Nairobi, and later to Zambia.

While in Nairobi, Dr. Rugunda was hosted by the family of the late Prof. Dani Nabudere in Muthaiga, an upscale suburb of the city. He recalls that Prof. Nabudere’s wife even paid his travel costs during that difficult period.

The Bakiga and Bagisu belong to the Highland Bantu cluster and share numerous cultural, linguistic, and physical characteristics. Both communities are generally short and stout, and they share place names and vocabulary with similar meanings.

For instance, sub-counties in Bududa such as Bushika and Bukigai mirror names found in Kigezi. Names like Namaloko in Bugisu and Nyamarago in Rukiga both denote places associated with witchcraft. There is also Kigezi in Mbale District and the Kigezi region in Kabale.

Both communities recognize a prophetic bird known among the Bakiga as Kamushungushungu believed to provide spiritual and astrological guidance. Among the Bamasaaba, a similar bird exists under a different name and is consulted for direction, including locating water sources in forests.

Linguistic experts estimate that Rukiga shares nearly 70 percent similarity with Lugisu. Common words include umukhanda/kumwanda (path), echiswani/shifanani (picture), and chibusi/khabusi (a matooke variety). Even the name Ruhakana, meaning argument or disagreement in Rukiga, corresponds to Khuwakhana in Lugisu.

An unverified theory among the Bamasaaba suggests that some Bakiga may have originated from Bugisu and fled practices such as Imbalu, later adopting Christian names to evade recognition. This theory merits deeper academic research.

Many Bakiga visiting Bududa, especially in Bukigai and Bushika, openly say, “We are home; we are one people.”

Dr. Rugunda and successive governments have supported the Natolo Masaba family, including state scholarships for descendants and public appointments, notably Rose Mutonyi, a former Resident District Commissioner of Masaka.

Dr. Rugunda maintains that the National Resistance revolution began in Bugisu. As Uganda approaches another election period, he urges the Bamasaaba to continue supporting the revolutionary cause.

Today, Dr. Ruhakana Rugunda, Chancellor of Gulu University and a Presidential Advisor, stands alongside President Yoweri Museveni as one of the most politically successful figures to emerge from that revolutionary generation.

The author is Steven Masiga, Spokesperson of the Bugisu Cultural Institution.

Disclaimer: As UG Reports Media LTD, we welcome any opinion from anyone if it’s constructive for the development of Uganda. All the expressions and opinions in this write-up are not those of UG Reports Media Ltd. but of the author of the article.

Would you like to share your opinion with us? Please send it to this email: theugreports@gmail.com.